Pancake Day Traditions

Why do we eat pancakes on Shrove Tuesday?

Shrove Tuesday, also known as Pancake Day, is the traditional feast day before the start of Lent on Ash Wednesday.

Join Food Historian Sam Bilton as she explores the history of the celebration, and details an 18th century recipe for a pancake pie you can try making at home – the ultimate Shrove Tuesday treat!

If you fancy something simpler, you can also head to the English Heritage YouTube channel and try Mrs Crocombe’s Victorian pancake recipe.

Why do we eat pancakes on Shrove Tuesday?

In Christian traditions, the 40 days before Easter are known as Lent, and they mark the time that Jesus spent fasting in the desert. Traditionally, Christians would mark the period with prayers and fasting, abstaining from a whole range of foods, including meat, eggs, fish, fats and milk. The word ‘shrove’ comes from the old Roman Catholic practice of being ‘shriven’ – meaning to confess one’s sins. The shriving bell would be rung on Shrove Tuesday to call people to church to confess.

Before Lent could begin in earnest, all edible temptations needed to be removed. This took place over a period of days known as ‘Shrovetide’. Meat such as bacon would be eaten up on ‘Collop Monday’ (a collop is a thin slice of meat). And on Shrove Tuesday eggs, butter and stocks of fat would be used up. One of the easiest ways to dispose of these items was to turn them into pancakes or fritters, a custom which continued long after the Church of England separated from the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century.

The Monday and Tuesday before Lent were periods of great festivity before the coming days of abstinence. Children would go ‘Shroving’ or ‘Lent-crocking’ on Shrove Tuesday (or the night before), knocking on their neighbours’ doors and singing:

'We be come a-shroving,

For a piece of pancake,

Or a bite of bacon,

Or a little truckle of cheese

Of your own making'

Or on Collop Monday:

'Once, twice, thrice

I give thee warning

Please to make some pancakes

‘Gin tomorrow morning'

Sometimes they would bring shards of crockery or stones with them to throw at householders who refused to give them anything!

When is Pancake Day?

Like Easter, Shrove Tuesday – now better known as Pancake Day – occurs on a different date each year because it is calculated by the cycles of the moon. While it’s already a little confusing, in the early days of Christianity in Britain it was far worse.

Before the 7th century there were two methods for calculating the date for Easter. One originated from Roman missionaries who established what is now Whitby Abbey. The second came from the Irish or Celtic tradition which – in the 630s – used the island of Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumberland as their chief mission centre.

Whitby Abbey was where the Synod of Whitby decided, once and for all, how the date of Easter should be calculated.

Whitby Abbey was where the Synod of Whitby decided, once and for all, how the date of Easter should be calculated.

Both used the lunar calendar, but had two different methods of calculation. This meant that the Roman and Celtic Easters fell on entirely different dates, which caused confusion for early Christians. In 664 the Synod of Whitby declared that the Roman method would be used to establish the date for Easter, and is still used by the Church of England today.

What do you have to give up during Lent?

Meat and dairy were outlawed during Lent, but Christians could eat fish, bread and vegetables. Fish was considered a virtuous food, on account of two of Jesus’ apostles being fisherman. Most of the fish consumed at this time, like herring or cod, would have been salted to preserve it. Dairy products were replaced with almond milk and butter. Spices were permitted to flavour food, but the absence of meat and dairy meant the Lenten diet could be pretty monotonous.

Even outside of Lent, monks already had a pretty restricted diet by modern standards, thanks to the Rule of Benedict. This was a set of guidelines used to govern monastic life. It dictated how a monastery should be run, what the monks could wear and the amount of food provided. Walter Daniel, a 12th century monk from Rievaulx Abbey, described the monks’ regular diet as a pound of bread and a pint of beans daily. This was to be consumed over two meals, although from Easter to September monks were allowed a third meal during the evening.

The refectory at Rievaulx Abbey, where the monks would have eaten their meals

The refectory at Rievaulx Abbey, where the monks would have eaten their meals

The Rule of Benedict forbade the consumption of meat from quadrupeds (animals with four legs) at all times during the year, so monks had a largely vegetarian diet. During Lent, their diet was even stricter. The first Monday after Lent, most monasteries observed a total fast. From the second week of Lent some monastic orders decreed that only raw vegetables and bread could be eaten.

By the 12th century things had become more lenient. It had been decided that the rule about eating meat didn’t include birds, so things like chicken could be eaten. Even bacon and offal could be on the monks’ menu – they weren’t regarded as ‘real’ meat.

Outside monasteries it was less strict, but still some lay-people developed liberal interpretations of what foods could be eaten during Lent. Beaver tail was allowed because these mammals live near rivers. Waterfowl, such as ducks, were cunningly dubbed ‘barnacle geese’ as it was believed these birds hatched from barnacles.

The Origin of Pancake Races

As well as giving up “luxury” foods, the faithful were expected to forego fun pastimes such as dancing and playing games like football. Therefore, Shrovetide (the four days preceding Lent) was a time for merriment.

A legacy of these festivities is the pancake race. Dating from around 1445, legend has it that a local woman heard the shriving bell while she was making pancakes and ran to church in her apron, still clutching her frying pan.

Recipe for a Pancake Pie

The following 18th century recipe is taken from Charles Carter's The Complete Cook (1730). Whilst it is not given as a pre-lenten dish, it is a novel way to present pancakes. There's also a 21st century version below for you to try.

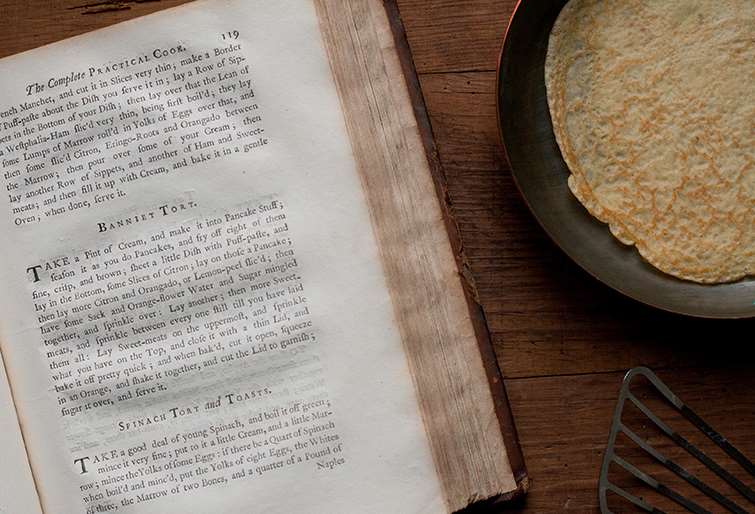

Banniet Tort (18th Century Version)

'Take a pint of cream, and make it into Pancake Stuff; season it as you do pancakes, and fry off eight of them fine, crisp, and brown; sheet a little dish with Puff-paste, and lay in the bottom, some slices of citron; lay on those a pancake; have some sack and orange-flower water and sugar mingled together, and sprinkle over: Lay another; then more sweetmeats, and sprinkle between every one still till you have laid them all: Lay sweetmeats on the uppermost, and sprinkle what you have on the top, and close it with a thin lid, and bake it off pretty quick; and when baked, cut it open, squeeze in an orange, and shake it together, and cut the lid to garnish; sugar it over, and serve it.'

A recipe for the ultimate pancake pie – Banniet Tort – from The Complete Practical Cook

A recipe for the ultimate pancake pie – Banniet Tort – from The Complete Practical Cook

Banniet Tort (21st Century Version)

Pancakes

• 110 g plain flour

• 2 large eggs

• 200g cream or whole milk mixed with 75g water

• 50g unsalted butter, melted

Filling

• 500g block puff pastry

• 110g candied citron (or substitute for mixed peel)

• 110g candied mixed peel

• 4 tbsp sweet sherry

• 2 tsp orange blossom water

• ¼ tsp ground cinnamon and a pinch of grated nutmeg (optional)

• Juice of 1 orange

• 80g caster sugar

• Icing sugar to serve

1. Sift the flour into a large, wide mouthed jug. Make a well in the centre then break in the eggs. Using an electric whisk beat the eggs into the flour gradually adding the cream and water mixture. Finally, stir in 1 tbsp of the melted butter (reserve the rest for frying the pancakes).

2. Heat a 18cm frying pan over a medium heat. Brush with melted butter then pour in a thin layer of the pancake mix. Cook for a minute or two until golden then flip over to cook the other side. The mixture will yield more pancakes than you need for this recipe.

3. Pre-heat the oven to 180℃.

4. Roll out the two thirds of the pastry to a thickness of 3mm and use it to line an 18cm round, sandwich tin.

5. Blend the sherry, orange blossom water, spices (if using), and orange juice together (I find it easier to add the orange at this stage than after the pie is baked). Mix the two types of peel together.

6. Sprinkle ⅛ of the peel over the base of the pie case followed by 1 dessert spoon of caster sugar and 1 tbsp of the sherry mixture. Cover with a pancake and repeat the process (a bit like making a lasagne) until you have used eight pancakes. Finally roll out the remaining pastry to make a lid for the pie, wetting the edges and pressing down to ensure it sticks to the case. Make a small hole in the top of the pie to allow the steam to escape. Bake for 20-25 minutes until golden brown. Allow to cool slightly for 10 mins or so before serving. To serve, dust the pie with icing sugar and cut into slices, perhaps with some whipped cream on the side.