The Real Story of Bonfire Night

Why we remember the 5th of November

Remember, remember

The fifth of November

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot

I see no reason

Why Gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot

Guy Fawkes Night makes an annual appearance in the English calendar every 5th of November, inviting revellers to light bonfires and fireworks across the nation as the autumn officially kicks in. But the roots of this centuries-old tradition is much more than an evening of sparks and illumination.

In this article, we’ll explore everything you need to know about the 5th of November, from Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot to the story of how Bonfire Night has changed over the centuries. It’s a story of rebellion, religion and riot – so grab a toffee apple and a sparkler, and settle down to find out more.

Over 400 years on from the failure of the event we know today as the 'Gunpowder Plot', the 5th of November is still a key date in the British calendar.

According to Google Trends, it’s most popularly known as ‘Bonfire Night’ rather than ‘Fireworks Night’ or ‘Guy Fawkes Night'. And even though Halloween might have overtaken it as our most popular autumn festival, it doesn’t show any signs of disappearing just yet.

Every year in the first really long dark nights of autumn – and after the trick-or-treaters have come crashing down from their sugar highs – the skies above our villages, towns and cities are lit up with fireworks. Children crane their necks to marvel at the sparkling, whooshing displays of light and colour, and our pets cower behind the sofas as the air cracks with the bangs and snaps of expensive pyrotechnics. In fact in 2017 alone, £155m was spent on fireworks for the celebrations, according to Mintel.

But why do we still celebrate a failed religious plot from four centuries ago with an annual festival of fireworks? Why is Guy Fawkes – who wasn’t even the plot’s mastermind – one of the most infamous figures in English history? And is there anything else we should remember, remember when we celebrate the 5th of November?

Image: Guy Fawkes night © Sally and Richard Greenhill and Alamy Images

On the night of the 5th of November 1605, 36 barrels of gunpowder were discovered hidden behind a pile of firewood in a storeroom beneath the Palace of Westminster. With them, guards found a man calling himself John Johnson.

They found fuses in Johnson's pockets, and swiftly arrested him. He held out for days under the pain of intense torture, but eventually he confessed.

His real name was Guy Fawkes and he, along with his fellow plotters, hoped to spark a Catholic uprising by blowing up parliament and everyone in it – including King James I and many of his leading nobles.

Image: Guy Fawkes is arrested in the Houses of Parliament © Pictorial Press Ltd and Alamy Images.

Background to the Gunpowder Plot

Before the 16th century, like its European neighbours, England was an unquestionably Roman Catholic country.

Almost everyone, from the monarch to ordinary men and women, looked to the pope as Christ’s ultimate representative on earth. Anyone who questioned the teachings or practices of the established Church ran the risk of being condemned as a heretic. Even translating the bible, or any other religious text from Latin, into English was seen as an outrageously radical act.

The dominance of the pope and the Roman Catholic Church came under increasing political and theological attack during the 16th century, a process which culminated in a movement now known as the Reformation. Protestantism – a form of Christianity which rejected various Roman Catholic doctrines – rapidly gained ground across northern Europe.

At first Henry VIII, England’s king from 1509 until 1547, stoutly defended Catholicism, even receiving special recognition from the Pope in 1521 with the title ‘Defender of the Faith’. But later in the 1520s the pope refused to grant Henry an annulment from his marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. The king was desperate for an heir, and infatuated with another woman, Anne Boleyn. Frustrated by the church at every turn, eventually he declared himself Supreme Head of the Church in England, and officially broke from Rome in 1534.

Henry VIII with Anne Boleyn and Pope Clement VII © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd and Alamy Images.

Henry VIII with Anne Boleyn and Pope Clement VII © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd and Alamy Images.

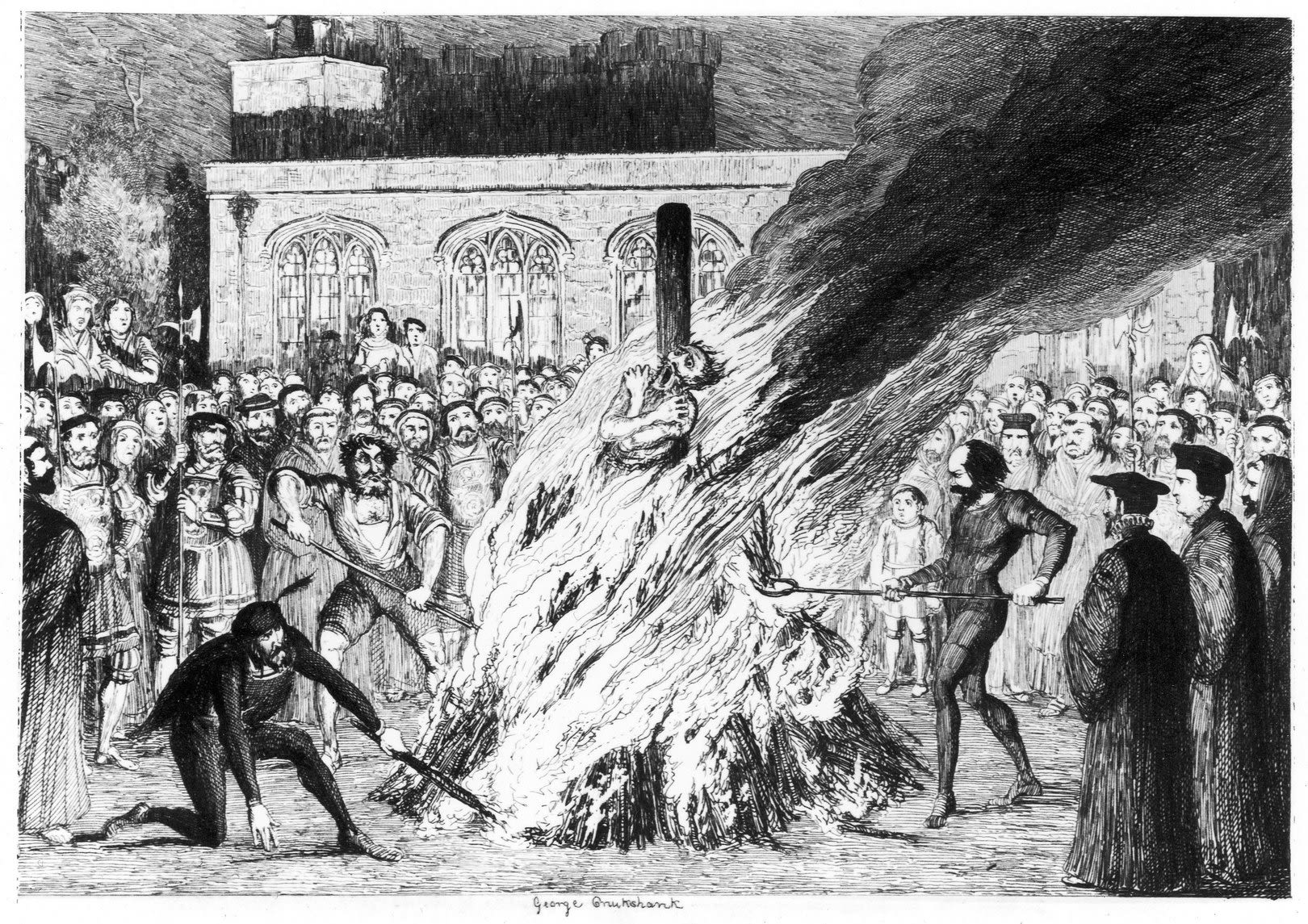

Although never really a Protestant himself, Henry closed England’s monasteries and stripped them of their lands and assets. His son Edward VI was raised a Protestant and pushed on with reform during the six short years of his rule (1547-1553), but Edward’s sister and successor Mary was a staunch Roman Catholic. Her rule witnessed a short, sharp attempt to reverse the Reformation in England. Most notably, and to the dismay of many, she had many Protestants burned at the stake, from leading churchmen to ordinary men and women.

However Mary’s rule was cut short by her death at the age of 42, and her sister Elizabeth restored a moderate form of Protestantism in England, known as the Elizabethan Settlement. Attendance at church became mandatory, and Catholicism was driven underground once again.

In the decades after Mary’s death, the people executed were widely celebrated as martyrs, including in John Foxe’s popular book Acts and Monuments (1563). The stories of their brutal deaths became a black stain on the reputation of Mary and English Catholicism, and were used to good effect by anti-Catholic agitators and propagandists.

The ‘optics’ of Catholicism in England were damaged by other events. There was a failed Catholic uprising in 1569 and a foiled plot to assassinate the now reigning Elizabeth I and replace her with her cousin, the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots. In 1570, Pope Pius V even excommunicated Elizabeth, absolved all her subjects from allegiance to her, and declared that anyone obeying her laws was likewise to be excommunicated. There was also the threat of the Spanish Armada in the 1580s, a failed coup in 1601 and widely shared reports of Catholic atrocities in Europe, including massacres of Protestants in France and Antwerp.

Catholics became viewed as a kind of ‘enemy within’ during this time – regarded as suspicious and generally up to no good. But Catholicism remained popular among the English gentry, many of whom worshipped in their own homes. For most of them, they felt their belief was a private matter, and they remained loyal to the Crown, not wishing to overthrow the regime.

But not for all.

Images: Execution of religious radical Edward Underhill during the persecution of Protestants under the reign of Queen Mary I © Granger Historical Picture Archive and Alamy Images and Elizabeth I in 1588 © Historical Images Archive and Alamy Images.

The Plotters

James I (James VI of Scotland) came to the English throne in 1603 and signed a peace treaty with Catholic Spain in 1604. For some Catholics, this was a terrible blow to their hopes that Spain might invade England and re-impose Catholicism.

On Sunday 20th May 1604, a group of Catholics met at the Dog and Duck pub near the Strand in London. These men were Robert Catesby, Thomas Winter, John Wright, Thomas Percy and Guy Fawkes – mostly members of the gentry, and all devout Catholics.

The conspirators involved in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 © De Luan and Alamy Images

The conspirators involved in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 © De Luan and Alamy Images

Catesby, a veteran of the failed coup of 1601 we mentioned earlier, was the plot’s charismatic mastermind. Tall, handsome and persuasive, he told the gathered men that he had a plan to blow up the king and his parliament. Despite some reservations, all five swore an oath on a prayer book, and they began to plot.

Robert Catesby may have been the driving force behind the plot, but Guy Fawkes was the man given the responsibility of lighting the fuse. So what do we know about him?

Fawkes was born in 1570 in York. His father was a staunch protestant, but he died in 1579 and Fawkes' mother married a Roman Catholic. It’s thought that Guy converted under his stepfather’s influence. In 1592 he sold the small estate his father had left him and went to the Low Countries to fight for Spain against its Protestant enemies. He became a well-liked, highly skilled soldier, and during his time fighting on the continent he probably became familiar with gunpowder and explosives.

Another of the plotters, Thomas Percy, was a minor member of the powerful Percy family, which had historic links with many English Heritage sites including Warkworth Castle, Sawley Abbey, Prudhoe Castle, Spofforth Castle and Wharram Percy Deserted Medieval Village. Percy’s patron was his relative and head of the family, the Earl of Northumberland, who – although officially a protestant – was widely regarded as a supporter of the Catholic cause.

By October 1605 a handful of other plotters had been brought into the conspiracy. Most were also members of the Catholic gentry. Among them was Francis Tresham, the son of Sir Thomas Tresham, a leading Catholic gentleman who built the remarkable Rushton Triangular Lodge in Northamptonshire as an eccentric and expensive expression of his faith. Thomas Bates, Catesby’s servant, also joined the plot after he accidentally learned of it.

The plotters now numbered a rather inauspicious 13.

Image: An etching, c.1606, showing all the conspirators in the plot to blow up the English parliament © IanDagnall Computing and Alamy Images.

The Plot

At its heart, the plot was a simple one: to blow up the Palace of Westminster during the opening of Parliament, thereby killing everyone inside – including King James I and his heir Prince Henry.

What they intended to do next is less clear, but it seems that with James dead and the country in chaos, some of the plotters would lead a pro-Catholic uprising in the Midlands. They would take hold of James’s young daughter Elizabeth, who was in Coventry, and install her as queen with a Catholic nobleman ruling on her behalf. Therefore, they hoped, England would be delivered back into the arms of Rome.

The plotters were able to get hold of gunpowder with relative ease – the end of the war with Spain meant there was plenty of it available on the black market. A bigger issue was getting it close enough to the Palace of Westminster.

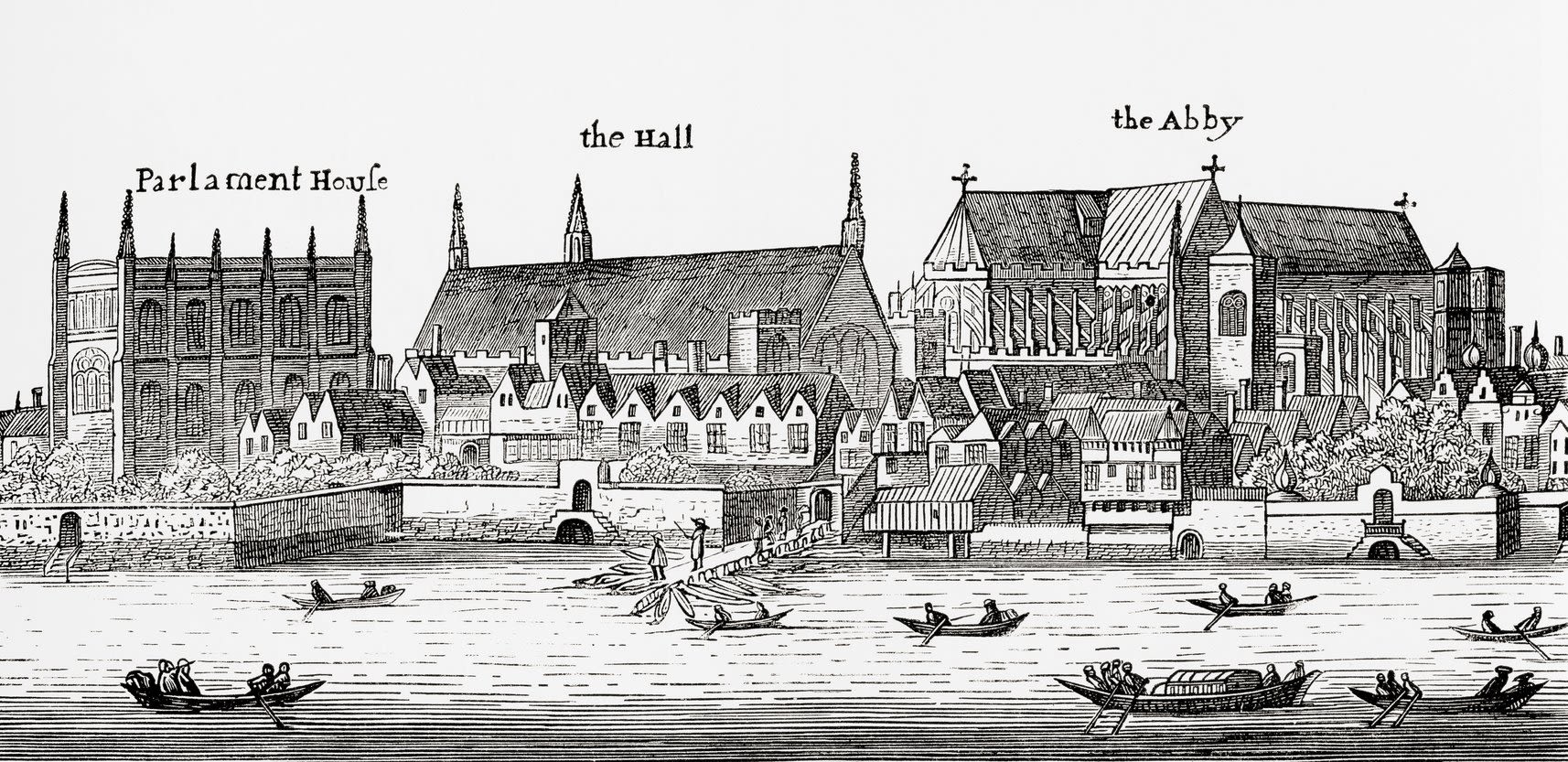

At first the plotters stored it in a house near the Palace which Thomas Percy managed to sublet from other Catholics. Guy Fawkes, the man in charge of the explosives and an unfamiliar face to most in Westminster, assumed the identity of John Johnson, a servant of Percy’s. In March 1605 an even more convenient piece of real estate became available – an undercroft or storeroom beneath the House of Lords.

The Houses of Parliament of the early 17th century were nothing like the Houses of Parliament today. The buildings had been added to and repaired piecemeal between the 12th and 17th centuries. The Lords met in a large room built in the 13th century as the Queen’s bedroom, and it was in one of the dark rooms underneath it that Fawkes placed the barrels of gunpowder. There was little security, and the buildings were a warren of meeting rooms, apartments, shops, wine-merchants and even taverns – making it reasonably straightforward for the plotters to stash 36 barrels of gunpowder in their undercroft.

Now the plotters just had to wait for their chance - the opening of Parliament on 5th November.

Image: Westminster, London in the 17th century © Hilary Morgan and Alamy Images.

Foiled!

Guy Fawkes made his penultimate check on the gunpowder on 30 October 1605. He found nothing amiss with the explosives, but nevertheless, the plot was beginning to unravel.

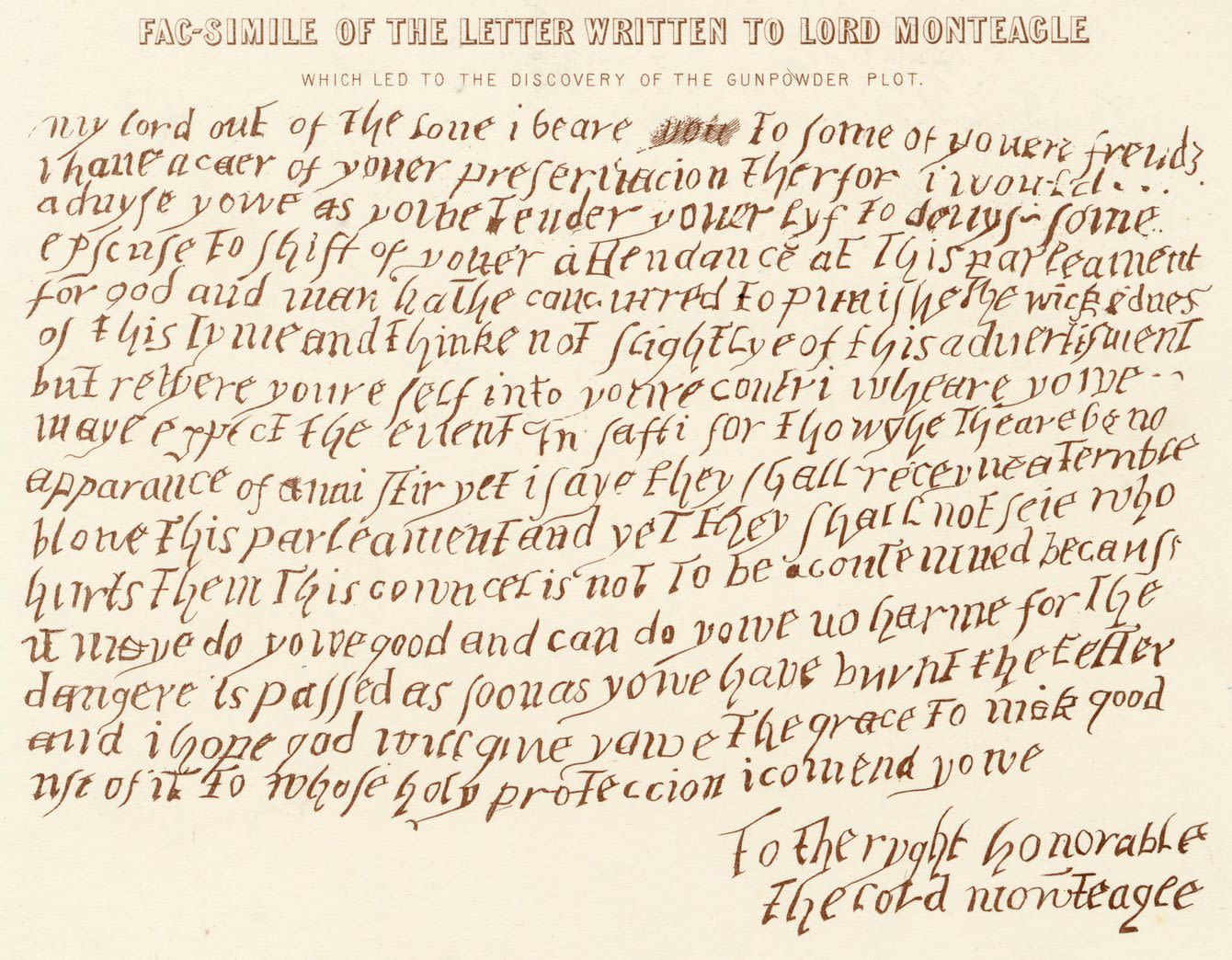

A few days earlier, Lord Monteagle, a Catholic sympathiser and former Catholic himself, received an anonymous letter. It read:

‘My Lord out of the love I bear to some of your friends I have a care of your preservation. Therefore I would advise you as you tender your life to devise some excuse to shift off your attendance at this Parliament, for God and man hath concurred to punish the wickedness of this time…they shall receive a terrible blow this parliament and yet they shall not see who hurts them.’

Although various names have been put forward, it’s likely that the letter came from Sir Francis Tresham, who was Monteagle’s brother-in-law.

Whoever wrote it, the author asked Monteagle to burn the letter once he’d read it – but instead he took it straight to King James’s right hand man, the Earl of Salisbury, who decided to inform the king on his return from a hunting party. One of Monteagle’s servants got word to Catesby that the plot had been betrayed, but he convinced his fellow plotters to continue, arguing that the letter was too vague to threaten their plans.

On the night of the 4th November, King James ordered a search of the Palace of Westminster, headed by the Earl of Suffolk. During their search they came across Guy Fawkes in the undercroft, and were surprised by the amount of firewood being stored there. They left, but soon learned that the space was being rented by Thomas Percy, which added to their suspicions. James ordered a second search headed by Sir Thomas Knyvett.

Sometime around midnight –perhaps in the early hours of the 5th – Knyvett went back to the undercroft, poked around the firewood and found the gunpowder. He arrested Fawkes, who had fuses with him, and a warrant was issued for Percy’s arrest.

Images: Letter to Monteagle © Chronicle and Alamy Images and Lord Monteagle receiving the anonymous letter revealing the Gunpowder plot © Historical Images Archive and Alamy Images.

Death of a Conspirator

Guy Fawkes was immediately questioned – even King James interested himself with the case and process.

Over the course of the 6th and 7th, Fawkes’ resolve was ground down by intense questioning and brutal pain. The signatures on his first and final confessions tell a story of a man pushed to the brink of physical pain and mental collapse.

Guy Fawkes' signature, before and after torturing © Pictorial Press Ltd and Alamy Images.

Guy Fawkes' signature, before and after torturing © Pictorial Press Ltd and Alamy Images.

Thanks to Fawkes' confessions and information from various intelligence networks, investigators uncovered the names of the other plotters and quickly moved to arrest them. Most had fled to the Midlands, where they tried and failed to rouse any kind of uprising.

On 8 November a core group of eight plotters made a last stand at Holbeach House in Staffordshire, but against a force of 200 men they stood no chance. Most were killed or wounded – Catesby and Percy were both hit by the same bullet, and they died of their wounds. The survivors were arrested, and all the remaining plotters were rounded up and put on trial.

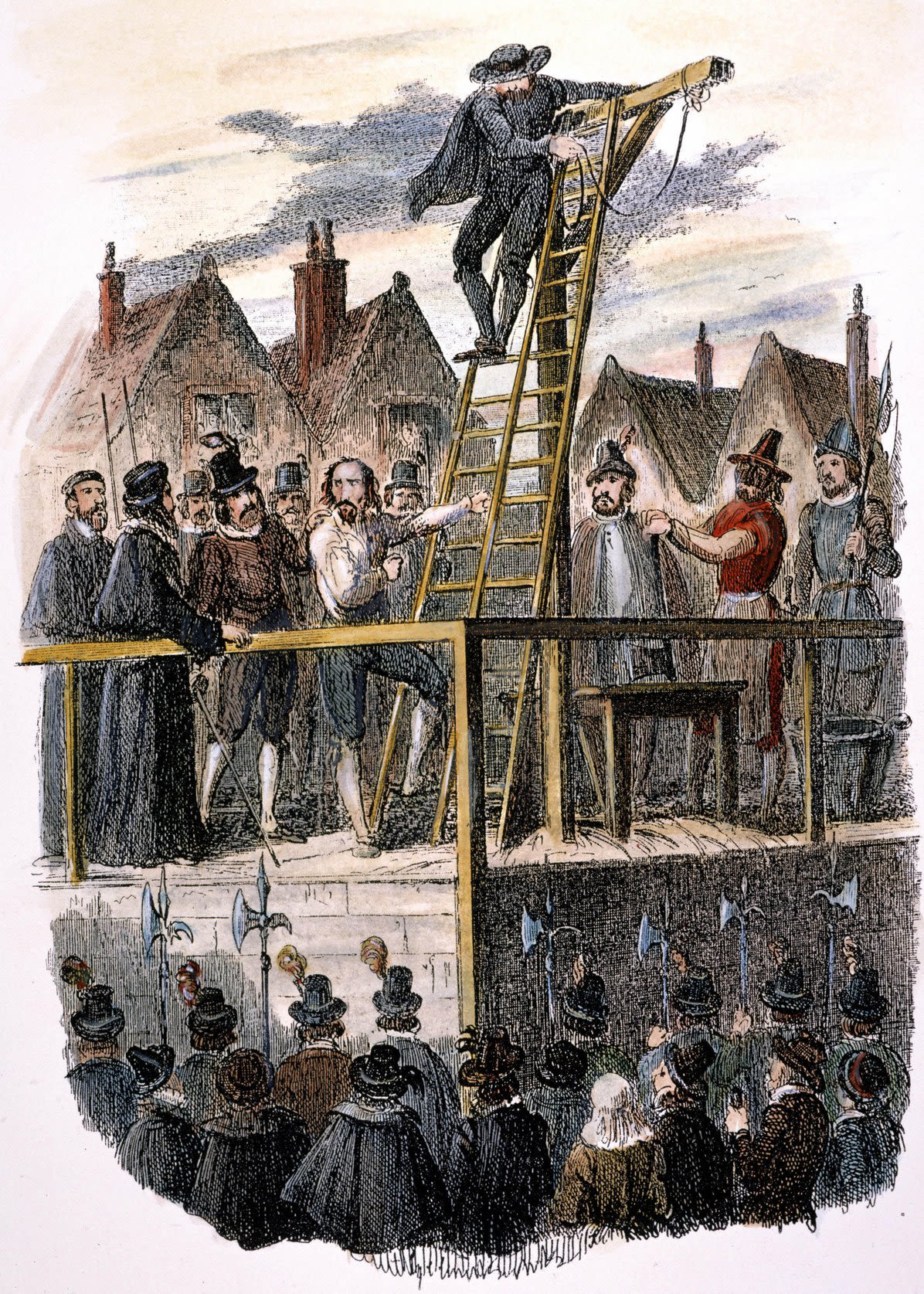

Each was found guilty and sentenced to a traitor’s death by the grisly ordeal of hanging, drawing and quartering. The men were hanged, then cut down (still alive) and castrated, dismembered and beheaded. Their bodies were cut into quarters and displayed for all to see – and for birds to feast upon. According to accounts, all faced their fates bravely.

Fawkes, by now brutalised and broken, was spared further agony when his neck broke during his hanging. He died instantly.

The execution of Guy Fawkeson 31 January, 1606 © Granger Historical Picture Archive and Alamy Images.

The execution of Guy Fawkeson 31 January, 1606 © Granger Historical Picture Archive and Alamy Images.

A Fiery Legacy

The plot became part of England’s national story almost immediately. The mood of the time was that the discovery of the plot was, along with the defeat of the Armada and Elizabeth’s long life, another sign that the English were favoured by God.

In January 1606 Parliament passed ‘An Act for a Public Thanksgiving to Almighty God every Year on the Fifth Day of November’, making it mandatory for every church in England to hold a special service on 5 November each year – at which attendance was, at least in theory, compulsory. Many sermons struck an anti-Catholic tone.

In the decades after the plot, other forms of celebration began to accompany this religious commemoration. Although evidence is patchy, records suggest that they were widespread, with bonfires and bellringing and sometimes official artillery salutes and fireworks. Popular accounts of the plot were published and in a 1614 play by Ben Johnson a puppeteer boasts that The Gunpowder Plot is ‘a get-penny’ – ie, a 16th-century blockbuster, and his most popular show.

Some years later, in 1660, parliamentarian and diarist Samuel Pepys recorded that:

‘The 5th of November is observed exceeding well in the City; and at night great bonefires and fireworks’.

A year later Pepys went to the Dolphin with his brother and a friend where they ‘sate late and drank much, seeing the boys in the street fling their crackers’.

Since 1673 and up until around the 19th century some crowds have paraded an effigy of the Pope through the streets, strung up above a bonfire. This symbolised continuing prejudice towards Catholics. However during the French Revolution, English and Irish Catholics fought for Britain, which found itself on the same side as the pope.

And perhaps because of this, in around 1800, Guy Fawkes seems to have finally entered the picture as the bogeyman of bonfire night, rather than the pope. Fawkes was barely mentioned in 5 November sermons in the 18th century, and his name doesn’t feature in titles of books or tracts before 1800. But after that date his name begins to appear, and Fawkes seems to have quickly become a central character in English popular culture – often portrayed as a dashing, doomed anti-hero.

Modern Guy Fawkes Celebrations

In the 20th century the 5th of November became a much friendlier family event. It was common to see fireworks displays in back gardens as well as children wearing Guy Fawkes masks or carting around his effigy, begging ‘a penny for the guy’. As late as the 1950s it wasn’t uncommon for bonfires to spring up on the streets, particularly on bombsites, and people were used fireworks to cause a nuisance in back alleys and city streets. But, on the whole, the 5th of November has now been tamed, stripped of its religious meaning and since the 1990s has been somewhat overtaken by Halloween as the UK’s premier autumn celebration.

In many ways, Guy Fawkes has slipped out of the picture – it’s the bonfire and the fireworks, not Fawkes, which form the centrepiece of most community celebrations. Lewes remains a notable exception, and thousands of people flock to see the town’s elaborate effigies most years.

But Fawkes refuses to fade away entirely. In the 1980s writer Alan Moore and illustrator David Lloyd gave Fawkes a new lease of life – the anarchist hero of their graphic novel V for Vendetta wears a stylised Guy Fawkes mask. Thanks to the 2005 film version and its adoption by various campaigning groups, the mask has now become a symbol of anti-establishment protests across the world.

It’s unclear what Fawkes would have made of this, because in seeking to blow up Parliament, he and his fellow plotters were merely hoping to impose a different kind of establishment. But the symbol of Fawkes has long outstripped the reality of the man, and the way we celebrate the 5th has changed greatly over time, depending on the politics, culture and society of the day.

As with everything in history, each generation has and will remember Fawkes and the 5th of November in its own peculiar way.

Image: A 5th November fireworks display in England © Steve Allen Travel Photography and Alamy Images.